You are intrigued by Buddhist ideas, but you find any kind of belief or religion incompatible with your modern worldview? As a Buddhist and computer scientist, I try to explain why there’s no need for worry.

Mindfulness and meditation have received a lot of positive attention lately; their benefits for body and mind are confirmed by scientific studies and they are widely applied in secular environments, such as psychotherapy or coaching (take the Mindfulness-based stress reduction program for an example). These results could raise interest in Buddhism also among the rather mundanely wired folks – it is natural to ask where these practices come from and how they are used in their original context. People who have already made positive experiences with meditation might want to dig deeper and see what else Buddhism has to offer.

Now while the characterization of Buddhism as a religion, a philosophy or something entirely different very much lies in the eye of the beholder, there are undeniably religious elements inherent to Buddhism. First of all, Buddhism is described as one of the five world religions and is recognized as a religion in many countries of the world. Then, depending on the specific Buddhist tradition and school (there are surprisingly many of them), you find beliefs, myths and rituals. And here is where things are getting difficult for many. In the western world, religions are in an image crisis: On one hand, they are constantly misused for populism and radicalization around the world; on the other hand, we regard them as obsolete in the light of modern science.

In science we trust.

In the face of the advances it has brought us – medical treatments, global real-time communication, or the refrigerator, just to name a few practical examples – it is not surprising that our trust in science is enormous. But is scientific knowledge really the only valid type of knowledge? And what defines scientific knowledge anyway?

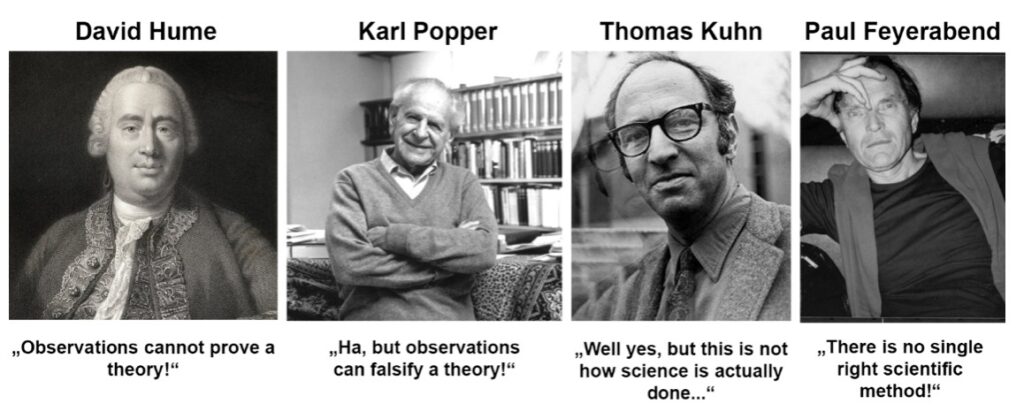

The popular perception goes something like this: science is objective, based on facts and logical reasoning, and free from dogma or personal opinions. Giving these statements a second thought, you might realize that things are not that simple. To illustrate, I will try to briefly sketch some related philosophical discussions that are still not settled today.

First of all, it is not clear how to obtain “objective facts” – via direct observation with your senses, through instrumental measurements, or with computer simulations? And how can we make observations that are completely independent from existing assumptions about the world? But even if we assume that we have objective facts at our disposal, deriving general knowledge from them is not straight-forward. In the 18th century, David Hume already noted that just because you observe some behavior of the world several times, there is no logical reason to believe that it will always be so. The classical example: you cannot claim that “all swans are white”, even after observing a million swans. This in turn motivated Karl Popper’s falsificationism: he proposes that in science, it is not possible to prove anything with certainty – but if a theory is wrong, it can be falsified. After observing a single black swan, we know that the theory “all swans are white” can’t be true.

While today the ideas of falsificationism are widely acknowledged, people that have studied how science is done in practice have found that it is not a good description of reality. Thomas Kuhn for example finds that in phases of “normal science” there are principles and assumptions that are never doubted; if observations contradict them, the error is rather sought in the observations (when observing a black swan in while “it is known” that all swans are white, you might first suppose that it has been just a trick of light, or a white swan covered in dirt…). Only when the contradictions become unbearably, a “paradigm shift” might take place.

Philosopher Paul Feyerabend takes it even further: in his famous essay “Against Method” he demonstrates that historically, the most important scientific discoveries were not made strictly following any one scientific method; and that intuition, personal conviction and opportunism plays a larger role than we would like to think. In his anarchistic theory of science he proclaims that there is no such thing as a universal scientific method, and there is no objective reason why any method should be inherently superior to other ways of gaining knowledge (such as astrology). Although his claims upset a lot of people (calling him “the worst enemy of science”), he couldn’t be conclusively refuted yet.

As you see, one can go very deep into this rabbit hole… But the only point that I want to drive home is this: we trust in science mainly because it has worked pretty well so far brought great advances to humanity; and not because it is a guarantee for truth.

The quest for truth

Although science can never be certain of truth, its pursuit of truth is certainly one of its defining properties. And here we find a striking parallel between science and Buddhism, where the quest for truth plays a fundamental role as well: Ignorance is the cause of suffering, and attaining the truth it is the goal of the Buddhist path.

In fact, the origin story of Buddhism can be easily framed as a classical research activity. Prince Siddhartha (that we today refer to as Buddha) observed the suffering present in the world outside of his palace walls, giving rise to questions he could not answer: why is there suffering in the world and how can it be eliminated? These questions were so pressing that he decided to abandon his life as a prince and set out to find answers. Over the next years, he visited various teachers of the time (a “state of the art review”) and thoroughly observed the world around and within himself. Finally, he came up with a profound theory about the nature of human existence and the universe, that he later taught to his followers.

Buddhas teachings include the four noble truths about the nature of suffering and its overcoming, “natural laws” that govern the world and not only encompass the physical, but also the moral domain (the law of dependent origination, and the concept of Karma), and other insights about the human mind (such as the idea of mindfulness mentioned at the beginning).

None of these teachings are grounded in any kind of divine revelation, but only in Buddhas meticulous investigations. Perhaps some of his methods (such as meditating under the Bodhi tree) were a bit different from what we would regard as “scientific” today but, to side with Feyerabend, this is not a quality feature per se. Like with modern science, the value of Buddha’s teaching shows in the large number of followers that found them convincing and useful – and still do so today.

The Buddhist path

Now, 2600 years later, Buddha’s teachings are conveyed in written Sutras and through numerous living Buddhist traditions. So, what does it mean to be a Buddhist practitioner today?

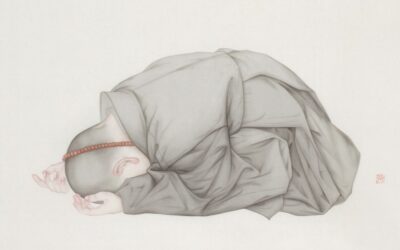

I would argue that Buddhism is very much a “hands on” religion – being literate in the Sutras is one thing, truly attaining them is something completely different. The teachings of Buddha, the Sutras, as well as the teachings given by living masters, are intended to guide us on our own quests for truth. They show the way, but we have to walk ourselves. Buddhism is not about believing what Buddha said – it is about becoming Buddha yourself. I like to imagine it like learning to play a musical instrument: You can study the music theory, you can have a teacher who shows you how it is done – bust the most important thing is to practice. As the years go by, you will master your instrument and get an understanding of music beyond words.

On the Buddhist path the instrument you want to master is your self: you slowly get better at handling your anger, desires and fears. You want to intuitively understand the “music” of the universe: What actions lead to which results? How should we act in each situation? How can we truly benefit others? In order to proceed on this quest, receiving teachings for guidance is very important; however, you have to apply them in practice and experience the effects in order to truly realize something. This is how Buddhist teachings are continuously validated on a personal level.

Science and Buddhism – a strong team

We have seen that the very cores of science and Buddhism are not as conflicting as it seems at first glance. Their methods might differ, but both are connected by a quest for truth. Science is less straight-forward than it seems – and Buddhism less mythical. Also, we must not forget that there are aspects of the world and human life that science has problems to grasp – like happiness, for example. In this context I would conclude that science and Buddhism are not conflicting, but complementing each other: Both are contributing to our understanding of the universe and can guide our actions towards a better world. Or like my master Ji Kwang Dae Poep Sa Nim once phrased it:

“When science and Buddhism come together, then incalculable power can be attained.” (Daily Sutra 9633, October 24, 2018)